By Michael McAllister

“Make sure you’re not getting played.” This advice comes from Paul Pate, Iowa’s Secretary of State and Commissioner of Elections, during a July edition of Iowa Public Television’s Iowa Press.

He was referring to the upcoming elections.

And he was referring to attempts by countries—he mentioned China, Iran, and Russia—to hack into the election processes of the United States in past elections.

Attempts to alter votes have not succeeded, Pate stressed.

Attempts to alter minds, however, perhaps have.

“They [Russian operatives] put messages and propaganda out there, creating doubt, and that’s a sad thing, and it’s very dangerous,” Pate continued.

To combat the disinformation campaigns of hostile sources, Pate advises, “Don’t take things at face value. You really do have to go beyond, say, ‘Just google it.’ You have to seriously look at … where you’re getting your information from.”

Fortunately, organizations do exist whose missions involve empowering voters with accurate information deliberately delivered, and one such organization both nationally and locally is the League of Women Voters.

From Silence to Suffrage

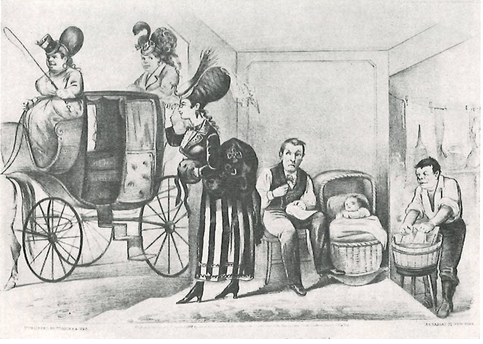

The very existence of women voters in the United States of America is a relatively recent phenomenon. Our country has been a country more than twice as long as its female citizens have had the right to vote.

That right did not come easy.

“The trail has been long and winding; the struggle has been tedious and wearying,” said Carrie Chapman Catt on February 13, 1920, in an address to the National Women Suffrage Association. At that time, the Nineteenth Amendment had been ratified by enough states that its ultimate passage was certain.

Mrs. Catt spoke with characteristic Victorian understatement, yet no voice could be more authoritative about women suffrage than hers. An Iowan since the age of seven, Catt had graduated from Iowa State University in 1880, the only woman in her class, and had distinguished herself as a feminist long before the term came into general use. For example, Iowa State reports that she organized military drills for girls, believing that military training should not be exclusively for men, and she was the first female student to deliver a speech before a debating society.

Catt’s work for women suffrage in Iowa began in 1887 when she joined the National American Women Suffrage Association. In 1900, she succeeded Susan B. Anthony as the organization’s president. She also pioneered woman suffrage internationally as one of the founders of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, and she broadened her progressive agenda to include work for peace, organizing the Woman’s Peace Party with Jane Addams in 1915.

Catt is described as “progressive but not radical” and the proponent of policies “delivered so as not to offend.” She dressed decorously, favoring blue, and was reported by the Mason City Globeto possess both “physical charms and intellectual endowments.” When Susan B. Anthony named Catt as successor, Catt responded to the assembled women, “Your President if you please, but Miss Anthony’s successor, never!”

By 1916, the woman suffrage movement had fractured, but Catt was able to unite groups with what became known as her “Winning Plan.” It called for women to work for suffrage at various levels, depending upon where their states stood on the matter, and it focused on suffrage apart from other issues that had become associated with the suffrage movement such as world peace and temperance. The plan is credited with earning the respect of President Woodrow Wilson, converting him to, in the words of historian John Meacham, “the side of the angels.”

Indeed, Meacham quotes a letter from President Wilson to Catt in which Wilson states, “I deem it one of the greatest honors of my life that this great event, the ratification of this amendment, should have occurred during the period of my administration.”

Catt stressed the need for women to work within political parties, yet she was wary of partisanship. Her address to the Congress of the League of Women Voters on February 14, 1920,–the event that marks the founding of the organization—expresses the dilemma in striking terms.

“Now, there are two kinds of partisanship. One is the kind that reasons out that a certain platform has more things in it that you endorse than any other and that this party has more possibilities of putting those things into practice than any other.”

The second type of partisanship, however, is “the kind to be afraid of.” Catt cited blindly supporting a party because “your grandfather and your father were” in the party as an example. “You don’t know what is your party platform or what your party stands for, but you are for it,” she explained.

Catt understood that what she was calling for would not come easy. “We must be non-partisan and all partisan,” she stressed, meaning that the League was to work within the country’s two-party system for legislation, that the organization would strive to accomplish “political things,” but that it would do its work to “teach this nation that there is something higher than the kind of partisanship that ‘stands pat’ no matter what happens.”

The League Comes to Grinnell

Grinnell’s League of Women Voters will mark its centennial in 2023. Current League President Terese Grant cites an article from the April 28thedition of the Grinnell Heraldthat details the formation of the League, whose mission was “the education of women to the intelligent use of the [voting] franchise, to work for legislation regarding maternity and child labor laws, and to remove the legal and political disabilities of women [through legislation].”

Grant provides a recap of the League’s work in Grinnell through the decades.

During the 1930s, the League focused on Citizenship Schools. Although women had earned enfranchisement, exercising the right to vote took knowledge and confidence. According to an article by Becky Cain, who served as President of the National League of Women voters from 1992 to 1998, Citizenship Schools were intended to educate women regarding, among other topics, national, state, and local voting issues (“if not too productive of acrimony”); the duties of elected officials; the role of money in politics; and the procedures by which legislation is enacted.

In Grinnell, Grant reports, Citizenship Schools were open to men as well as women and featured notable speakers such as Chester Davis, who served in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s cabinet as Director of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration.

In the decade of the 1940s, the Grinnell League maintained close association with Grinnell College in sponsoring events such as the International Affairs Institute, in 1941. Grant assesses it as being “lauded across the state especially because of its timely relevance to the war in Europe.”

Local affairs also attracted the League’s attention. In the 1950s, for example, the LWV focused on city government and helped establish Grinnell’s present city and city council system. Later, the League was instrumental in bringing about a parks and recreation commission and its director.

Grinnell’s Human Rights Commission also came into being because of LWV involvement.

Solid waste management, recycling, county land use, city ward reapportionment, school district realignment, housing needs, poverty—these are all issues that have captured the League’s attention from the 1970s to today, Grant notes. She quotes Carrie Chapman Catt who declared, “If the League isn’t five to ten years ahead of others in our identification of needs, then we should just disband.”

The League and the Law

“We envision a democracy where every person has the desire, the right, the knowledge and the confidence to participate,” reads the League’s vision statement. Therefore, Grinnell’s League often organizes and hosts informational meetings designed to educate.

“We are always looking for ways where we can be useful in Grinnell,” Grant states.

Grinnell’s LWV chapter is one of 11 in Iowa. Approximately 60 members are involved in Grinnell, including eight men, and throughout Iowa’s League chapters 15% of the members are men. Grant states that there has been talk of changing the League’s name to reflect the membership mix, but the present name is “too well known.”

While the League of Women Voters is nonpartisan, it does advocate when issues arise. It employs a lobbyist and encourages members to engage issues with questions and letters to elected officials and policymakers.

Recently, League efforts involving Iowa’s rejection of ballots from people mistakenly identified as felons have become known. On August 8, The Des Moines Register’slead article reported that the Iowa League of Women Voters and the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan institute that researches law and policy issues, advised Secretary of State Paul Pate by letter that Iowa’s ballot rejections “is believed to be in violation of federal law and must be remedied.” his comment is here and you can check out more commentary by lawyers on that website. You can also find out more at Flagler Personal Injury Group and get more insight.

The letter, dated June 13, was not intended for public release. The Registerstates, “it was inadvertently published with information intended for voter advocates.” Put another way, neither the Iowa League of Women Voters nor the Brennan Center sought to call attention to their conclusions beyond the bounds of the secretary of state’s office.

Terese Grant, President of the Iowa League of Women Voters, and Eliza Sweren-Becker, an attorney for the Brennan Center, signed the letter.

The Iowa law that denies felons an automatic reinstatement of their right to vote upon completion of sentences received attention in this year’s legislature when Republican Governor Kim Reynolds voiced support for a constitutional amendment that would automatically restore such rights.

Legislation to begin the amendment process was favorable until stalled and allowed to die in the Senate.

The issue that the Brennan Center-ILWV letter details refers to the National Voter Registration Act of 1993. If the Secretary of State’s office passes incorrect information to the counties, erroneously identifying voters as felons and causing their votes to be rejected, the office might be in violation of the law.

Moreover, Iowans “who wrongfully cast ballots due to inaccuracies or misinformation can face criminal prosecution,” the Registerreports.

The issue remains unresolved as of this writing, but it illustrates the League’s attention to detail and its commitment to the sanctity of the voting booth.

Praising Tactics as well as Triumph

When it became apparent that the Nineteenth Amendment would pass, Carrie Chapman Catt, speaking to the National Woman Suffrage Association on February 13, 1920, urged members to “be joyful today.”

“I beg you to celebrate the occasion with some form of joyous demonstration,” she declared.

Catt went on to celebrate not just the eminent victory but the way it had been achieved. “We should be proud, proud that fifty-one years of organized endeavor have been clean, constructive, conscientious.”

“Our army never resorted to lies, innuendos, misrepresentation,” she continued. “It never called its enemies names. It never accused its opponents of being free-lovers, pro-German and Bolsheviki.”

While these comments reflect the Victorian politesse of the time, they also exemplify Carrie Chapman Catt’s determination to reject blind partisanship, to avoid name calling, and to maintain civil discourse.

That desire continues today in Grinnell’s League, establishing the organization as a significant bulwark against the trend toward uncivility so prevalent in today’s political arena.

“I would like the League to take a role in helping the people in the two parties to not see each other as ‘the other’ or ‘enemies,’” Grant notes. “The current state of politics is so disturbing to me and I just hate to see this division.”

Grant sees the legislative coffees, held in February, March, and April each year, as places where polite questions are asked and civil exchanges of ideas are presented. The Grinnell League organized a meeting on the topic of civil discourse in the fall of 2018, but attendance was low. Still, Grant reports that efforts to address the issue of respectful communication continue.

“We need more of that—where people take the time to talk and, most importantly, to listen to each other,” she concludes.

The Grinnell League maintains a Facebook presence, and the Iowa League’s website may be reached at https://www.lwv.org/local-leagues/lwv-iowa.