How riots, rules, and poor office equipment made Iowa’s precinct caucuses first in the nation

By Michael McAllister

There are more pigs than people in Iowa, and now and then—every four years or so—more politicians than pigs. Or so it seems.

The Iowa caucuses draw the politicians, of course, and Iowa benefits in various ways. While campaign spending may not do a lot to boost Iowa’s economy directly, as reported by the Kansas City Starin January 2016, significant indirect benefits follow in the wake of candidate barnstorming.

For example, the Starquotes Iowa State economist Dave Swenson who cites “the state’s image” as the chief beneficiary of the caucus process.

All eyes on Iowa equates to an opportunity to showcase the state.

Still, politicians and staff workers, reporters and camera operators, volunteers and pundits have to eat, travel, and sleep; so restaurants and bars, gas stations and convenience stores, and hotels and motels are likely to reap a crop of currency.

Then, too, there is the matter of pride. Iowans are the first people in the United States to register a presidential preference. Husk that, Nebraska!

Candidates benefit also. The Iowa caucuses are not necessarily predictors, yet a good showing by a candidate—even a showing that does nothing more than beat expectations—can burnish a candidate’s fledgling reputation or stoke the fires behind an established figure.

In fact, the caucus process is complicated, even messy, and it determines electors, not candidates. And the old saying about not visiting a sausage factory if you like sausage comes to mind.

Nonetheless, the caucus system is ours.

But how did it all happen? How did the Iowa caucuses become the first official United States presidential preference event?

“We just kind of fell into it,” said Richard Bender, described in an Iowa Public Television documentary as “architect of [the] 1972 Iowa caucus system.”

Put another way, Iowa’s early caucus date happened not out of strategy by any political party but out of a combination of pressures—a need for reform, a quest for transparency, and the logistics of distributing information in the pre-digital age.

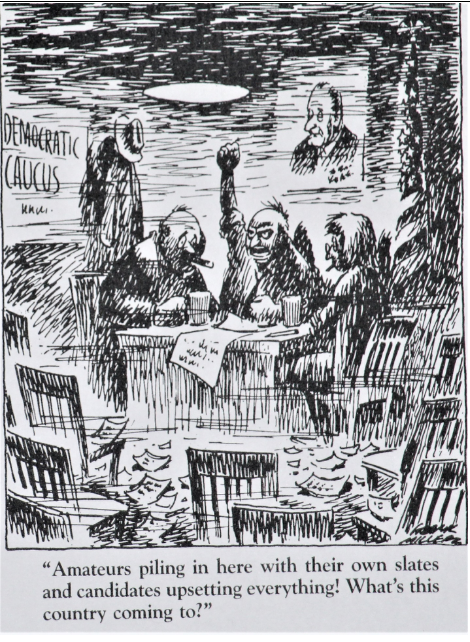

Frank Miller, editorial cartoonist for The Des Moines Registerfrom 1953 to 1983, registered a humorous take in 1968 on the spirit of political reform that led indirectly to Iowa’s first-in-the-nation status.

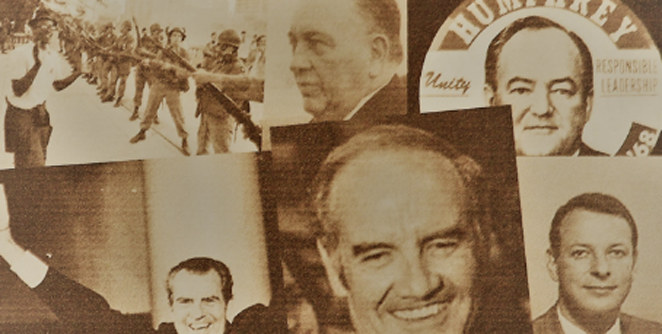

The caucuses we know today can be traced to 1968 and the chaos in Chicago that marred the National Democratic Presidential Convention late in August.

It was not a good year, 1968. Smithsonian Magazine calls it “the year that shattered America.”

In Vietnam, the Tet Offensive had defied the predictions by America’s military that, as General William C. Westmorland had recently stated, there existed “some light at the end of the tunnel.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in April. Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down in June. Demonstrations were staged throughout the country to protest America’s involvement in Vietnam and to further the civil rights movement. Often, these protests erupted in violence.

President Lyndon B. Johnson shocked the nation when he announced, on March 31, that he would not seek or accept “the nomination of my party for another term as your president.

The Democratic Party held its convention in Chicago beginning on August 26. It was a convention like no other. Americans watch unprecedented riots in the streets as police bashed protestors. Confusion inside convention headquarters did little to inspire faith in the Democratic Party.

“It was a horrible convention,” said Iowa’s David Yepson, then The Des Moines Register’spolitical reporter.

The party did emerge with a nominee, however: Vice President Hubert Humphrey. He had entered no primaries. His victory came “mostly through delegates controlled by party bosses,” according to SmithsonianMagazine.

Humphrey lost the election in a close race to Richard Nixon, and as the Democratic Party worked to revitalize itself, significant changes in the nominee selection process seemed in order.

In response, party officials established the Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection. Senator George McGovern of South Dakota and Representative Donald Fraser of Minnesota headed the commission, which quickly came to be called the McGovern-Fraser Commission.

The commission’s task was to eliminate the smoke-filled backroom, to turn delegate selection to a grassroots process, wresting selection from the hands of party bosses and placing it in the hands of the people. In addition, the commission was to establish rules that would insure an orderly 1972 Democratic National Convention.

The commission’s work not only strengthened the presidential primaries in several states but also energized precinct caucuses in Iowa.

In the past, Iowa’s caucus system called for gatherings in either March or April, and the system was perceived as under the control of party leaders. Reforms generated by the McGovern-Fraser Commission “radically changed presidential politics in the state,” according to Iowa Public Television.

Why did the caucuses move from March or April to January? It was a simple matter of logistics. Iowa Democrats needed to work in precinct caucuses, county conventions, district conventions, and state conventions before the national convention, which had been set by the Democratic National Committee for July 10, 1972—approximately 6 weeks before the 1968 convention.

Each step in the process required information to be printed and to be distributed to party operatives, and Hugh Winebrenner, former professor of history at Drake University and author of The Iowa Precinct Caucuses: The Making of a Media Event(first edition), notes that “the state party headquarters had severe physical limitations and very poor office equipment.”

To get material printed and distributed, the state party’s constitution called for scheduling events 30 days apart. Because the national party had set the national convention to begin on July 10, Iowa party officials had to count backwards from that date. Doing so, and allowing for 30 days between events, set the date of the Iowa precinct caucuses as not later than January 24.

Until then, the New Hampshire primary had been the first-in-the-nation presidential preference event.

Although the Iowa shift moved the state ahead of New Hampshire, the man who chaired the Iowa Democratic Party at the time, Cliff Larsson, “maintains there was no political intent in moving the caucus date forward,” Winebrenner writes.

Still, it wasn’t long before Iowa realized the prize it had unintentionally grabbed. As Larson puts it in an interview with Iowa Public Television, “We had a slow mimeograph machine, but we weren’t stupid.”

But what are caucuses without candidates? Iowa benefitted from media attention when George Mc

Govern, no longer a member of the McGovern-Fraser Commission, came to the state to campaign in 1972. His campaign manager, Gary Hart, saw the value of media attention early on and said, “We’re going to pay attention to them,” speaking of the Iowa caucuses.

McGovern’s efforts did not bring him a win in Iowa—that prize went to Edmund Muskie of Maine—but media attention, especially a piece in the New York Timesby R. W. Apple, bestowed credibility on the caucuses. For some, the real story was not Muskie’s win or McGovern‘s showing but the presence of the New York Timesin Iowa.

The state and the caucuses won significant attention during the next four years from a former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, when he campaigned heavily in the state and appeared to rise from relative obscurity, later to capture the party’s nomination. (He did not capture the Iowa caucuses, however; that honor went to “Uncommitted.”)

The Democratic Party after 1974 worked to encourage both candidates and media to come to the state, and the Republican Party moved its caucus date forward to match the Democratic Party’s. The parties set their caucuses for January 19 in 1976.

Early caucus dates were threatened in 1977 when the National Democratic Party stepped in, concerned about the expense of the now-lengthened campaign season. The state countered with legislation, and the early dates prevailed.

But challenges remain. California changed the date of its primary to March 3, 2020, a significant shift from its June 7 date in 2016. Texas is also eying an early date. NBC News declared late last year, “California and Texas look to become the new Iowa and New Hampshire.”

There are those who argue that Iowa does not deserve its first-in-the-nation status since it is not a demographically representative state. Other commentators blame the media for hyping caucus events beyond significance. The caucuses can boost a candidate’s reputation even if the boost is short lived: Pat Buchanan, second in 1996; Steve Forbs, second in 2000; Mike Huckabee, first in 2008; Richard Gephardt, first in 1988. A good showing in Iowa is no guarantee, and a poor showing is not necessarily a disaster, yet the general feeling is that a candidate needs to finish in the top third to be viable—the “three tickets out of Iowa” principle.

“The Iowa caucuses have a poor record of predicting presidents, but they play the important role of winnowing the field,” concludesThe Des Moines Register.

In 2020, Iowa precinct caucuses take place February 3.